by Stuart Masters

Advices and Queries no.35 – Respect the laws of the state but let your first loyalty be to God’s purposes.

In the authorised version of Quaker history it is received wisdom that James Nayler, although a man of deep spirituality with a significant gift for preaching and writing, was an unstable and ‘Ranterish’ character who brought the Quaker community into disrepute. This perspective assumes that it was Nayler’s conduct in Bristol in 1656 that forced the movement to exercise greater control over its more turbulent adherents by establishing a system of corporate structures and community discipline. I want to argue that modern Quakers should question this received wisdom by adopting a sceptical and critical approach to all narratives that seek to explain events in a way that blames the victims for the suffering and persecution they endure. I will try to do this with reference to the actions of Jesus in ‘cleansing the Jewish Temple’ and modern examples of civil disobedience.

Nayler’s Ride into Bristol

On a rainy Friday afternoon on 24 October 1656 James Nayler entered the City of Bristol accompanied by a small group of bedraggled followers. They led him on a horse as they waded through the muddy streets singing ‘Hosanna’ and ‘Holy, holy, holy, Lord God of Israel’. This was clearly and intentionally a re-enactment of Jesus’ entry into Jerusalem on ‘Palm Sunday’. However, like this biblical scene, Nayler’s re-enactment did not bear the hallmarks of a ‘triumphant’ display of earthly power. Instead it seemed to represent an inversion of the world’s expectations. Nevertheless, the entire party was arrested and taken to jail. Those in power within the English Commonwealth, who had become increasingly alarmed by the rapid growth and subversive nature of the Quaker movement, saw this as a perfect opportunity to crack down on Friends by making an example of Nayler. He was taken to London to be tried by Parliament for blasphemy even though this assembly had no legal jurisdiction to do this. The charge of blasphemy rested on the accusation that Nayler was claiming to be Jesus Christ. However, as his testimony to Parliament makes clear the Bristol event was an outward sign dramatising the Quaker belief that Christ had returned in spirit and would dwell within all who accepted him. He said:

“I do abhor that any honours due God should be given to me as I am a creature, but it pleased the Lord to set me up as a sign of the coming of the righteous one. . . I was commanded by the power of the Lord to suffer it to be done to the outward man as a sign, but I abhor any honour as a creature.â€

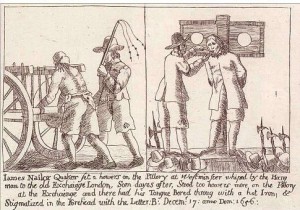

Despite this unequivocal statement, the political objectives of Parliament far outweighed any consideration of justice and Nayler was convicted of ‘horrid blasphemy’. Only narrowly avoiding execution he was sentenced to a particularly brutal form of punishment. This included being pilloried and receiving 310 lashes through the streets of London which very nearly killed him. He was pilloried again and had his forehead branded with a letter B for blasphemer and his tongue bored through with a hot iron. Following a largely ritualistic flogging in Bristol, he was imprisoned for an indefinite period at Bridewell. After his sentencing Nayler responded:

“God has given me a body; he shall, I hope, give me a spirit to endure it. The Lord lay not these things to your charge. pray heartily that he may not.â€

The case was used to maximum effect for propaganda purposes and in the aftermath Quakers suffered more intensive persecution at the hands of the authorities. Nayler was all but disowned by significant sections of the Quaker movement due to the alleged damage he had caused and for daring to challenge the leadership of George Fox (there had been significant conflict between the two men in the lead-up to the Bristol incident and Nayler’s followers were instrumental in pressing his leadership claims). Although Nayler was later released from prison and reconciled with the wider Quaker movement, his health was broken and he died in October 1660 after being robbed while travelling home to Yorkshire to visit his family.

Jesus Cleanses the Temple

Jesus’ ‘triumphal’ entry into Jerusalem represents the beginning of the end of his ministry. Shortly after this event, Jesus visited the Temple in Jerusalem which was the centre of Jewish worship and viewed figuratively as the ‘footstool’ of God’s presence. It is difficult to over-estimate the religious and political significance of this sacred place. Having witnessed what was going on in the Temple during his first visit, Jesus returned the next day and drove the money changers and all those involved in buying and selling from of the Temple courtyard accusing them of turning it into “a den of robbersâ€. It would appear that this action sealed Jesus’ fate. The Sadducees, who were part of the Jewish elite and collaborators with the Roman occupiers, decided that Jesus was a subversive and a threat to social order. In order to protect their power and privilege, he had to be neutralised. Not long after, Jesus was arrested by the Temple authorities who, in collusion with the Romans, had him executed by crucifixion. His followers scattered and the Jesus movement appeared to have been crushed. As we know however this was by no means the end of the story.

How do we respond to the actions of Jesus in the Temple courtyard? If we apply the approach traditionally used to interpret the ‘Nayler incident’ we will have to conclude that Jesus’ behaviour was irresponsible, blasphemous and downright provocative. It was bound to get him into trouble, endanger his followers and bring his movement into disrepute. He deliberately caused a disturbance within Judaism’s most sacred place and threatened social order in the circumstances of Roman military occupation. Was this not madness? Did Jesus have a death-wish?

Modern Non-violent Action

In the modern era we have seen many important examples of individuals and groups choosing to consciously break the law or contravene social conventions as a form of non-violent action.

The architect of modern non-violent resistance, Mohandas Gandhi, used a method of non-violent direct action he called Satyagraha in the struggle for Indian independence. In the Salt March of 1930 Gandhi organised a massive campaign of civil disobedience to protest about the British monopoly control of salt supplies. This involved a range of unlawful acts including tax resistance and led to beatings and imprisonments on a large scale.

In the US State of Alabama on 1 December 1955 a Black woman by the name of Rosa Parks refused a bus driver’s order, based on State law and practice, to give up her seat for a white passenger. She was arrested and jailed. This act of disobedience prompted the Montgomery Bus Boycott and galvanised the modern American Civil Rights Movement. In this struggle for racial equality many activists were beaten, jailed and murdered by white racists.

In 1986 the Israeli technician Mordechai Vanunu, outraged by his government’s covert development of nuclear weapons, passed information about this programme to the British press. He was then lured to Italy by a Mossad agent, where he was drugged, kidnapped and transported to Israel to be tried in secret for treason and espionage. Following his conviction he was imprisoned for 18 years. Much of this time was spent in solitary confinement. Since his release in 2004 he has suffered severe restrictions on his speech and movement.

How do we respond to the actions of these people? If we apply the approach traditionally used to interpret the ‘Nayler incident’ we will have to conclude that their behaviours were criminal, seditious, treacherous and knowingly designed to undermine law and order and social well-being. What they did was bound to get them into trouble, endanger their communities and bring their beliefs into disrepute. They deliberately broke the law and provoked conflict in sensitive and difficult circumstances. Was this not madness? Did they all have a death-wish?

Of course, how we respond to these examples depends on where we stand on the issues concerned. Quakers and many other people would regard Jesus, Mohandas Gandhi, Rosa Parks and Mordechai Vanunu as heroes, liberators, justice-seekers and role-models but to those in power they were dangerous, they were the enemy. They threatened the very values, beliefs and practices that bind societies together and they undermined the security and well-being of God’s favoured nation or empire.

Revisiting the 1650s

Throughout most of the 1650s the burgeoning Quaker movement waged a provocative but non-violent spiritual campaign (the Lamb’s War) against the established church and the Commonwealth Parliament. They disrupted church services, confronted the clergy, disputed with opponents in public, refused to show deference to their ‘superiors’, staged startling happenings such as ‘going naked as a sign’, and dispensed threatening prophetic warnings to those in power. Not surprisingly, they were regarded by those in power as a very serious threat to social order at a time of great political turmoil. This is why they made an example of James Nayler and used his actions as an excuse to persecute the Quaker community as a whole.

What provoked radical groups such as the Quakers was the failure of the commonwealth regime to deliver the promises made during the English Civil Wars that victory would lead to far-reaching social, political and religious reform. The expectation that a new society would be created based on greater equality, democracy and religious freedom was disappointed. For much of the period, the country was under military dictatorship, dissenting groups were persecuted and the army was busy slaughtering thousands of people in Ireland. In these circumstances to hold James Nayler responsible for his punishment and the persecution of the Quaker community is simply to blame the victim. Nayler’s behaviour at Bristol was entirely consistent with the essential character of the early Quaker movement. His actions involved no violence, no coercion and no threats to people or property. He simply enacted an outward physical sign representing what he had found to be true inwardly and spiritually.

Let’s Stop Blaming the Victim

It was those in power who illegally tried James Nayler and tortured him almost to the point of death. It was those in power who flogged Quakers in the market places, locked them in the stocks and the pillory, provoked mobs to attack them and threw them into disease-ridden dungeons at the mercy of brutal jailors. The time has come to stop blaming the victim and instead defend James Nayler as a Quaker hero, justice-seeker and role model.

This article was first published by Stuart Masters on his blog, A Quaker Stew. Visit http://aquakerstew.blogspot.co.uk/2012/03/why-do-we-blame-victim-in-defence-of.html to read the article on Stuart’s blog.

Stuart’s article is an admirable attempt to redress the negative take on the complex character of Nayler offered by Fox and later by Rufus Jones. I am, though, a bit uncomfortable with the urge to portray characters from history as ‘goodies’ or ‘baddies’, because I feel it does not allow for the complexity of the characters involved, their motives and their times. Those early Quakers were singular complex men and women in complex singular times. Religious upheaval, civil war, regicide, plague all contributed to a millinarian backdrop, which we may conclude bred much fear and concommitant anger.

The ‘going naked as a sign’, the disruption of church services, the wilful refusal to conform to social norms were all intentionally provocative acts that sought challenge in the very least, if not conflict. Nayler and his followers would probably have been a bit miffed if their staged entry into Bristol had been totally ignored (as i believe it was when they pulled the same stunt in Wells a bit earlier).

In addition to having fought in the civil war Nayler was no stranger to conflict – disputes with Howgill and Burrough as well as with Fox.

Surely the reality is that many of those early Quakers were, certainly by modern Quaker standards, a rather argumentative and disputatious (and somewhat theatrical?) bunch who sought to provoke, as committed young people are wont to do – though Nayler is forty years old by the time of his Bristol entry.

I suspect their motives were a mixture of justifiable anger and egotistical posturing – though I did not see it that way when I was engaged in similar activity as a young man! I am now 62 and less inclined to confrontation.

When we make a stand in order to assert a point – Mordecai Vanunu, Rosa Parks et al – we cannot know whether our action will generate an extremely punitive response. Jesus and the temple. But we’d better be ready for it.

I suspect the fear quotient is the deciding factor.

Thank you very much Stuart.

Dear David,

Thank you for your thoughtful comments. I agree that the first generation Quakers were a rather confrontational and argumentative lot. However, we must remember that they were consistently nonviolent and faced a regime that was slaughtering the Irish and regularly torturing people to death (it was still common practice to hang, draw and quarter those convicted of treason). It seems only fair to compare their behaviour to the values and practices of the time rather than to modern standards and expectations.

You are right to be sceptical of the simplistic use of ‘goodies’ and ‘baddies’ in explaining events. However, is it right to remain even-handed and neutral even when the facts point overwhelmingly to a different position. As Quakers today we have faced similar issues over the decision to support a boycot of products from Israeli settlements.

The circumstances surrounding the ‘Nayler incident’ are both complex and fascinating. I have written some additional material considering a range of factors that may have been at play. I may make available on my blog in due course.

I would maintain that, in context, Nayler’s nonviolent public sign was in many ways less provocative than the actions of Gandhi, Parks and Vanunu. To me he is a hero because of his deep spirituality shaped in the crucible of great suffering and hardship, his humbleness in seeking reconciliation with his community, and his willingness to forgive his enemies. These characteristics look quite Christ-like to me.

Shalom,

Stuart.

A timely effort to put the record straight and show what is still relevant. Problemsarise over the intermingling of religion and poitics. The examples you refer to all put their relious commitment first but in different ways and in different degrees. It has been suggested that Fox was hoping forsome some kind of political deal that would give Quakers more religious freedom and political influence and he blamed Nayler for making this more difficult. Perhaps it was Fox and not Nayler whgo was being unrealistic omn that occasion.

I have reservations as to what you say about Jesus. His entry into Jerusalem also attracted little attention at the time and you rathergive the impression that he created a major dosturbance in the vast outer courtyard of the Temple. His was a token action that went unnoticed by most people in a huge crowd. The Roman soldiers were ofn the lookout for trouble but saw nothing worth recording. The Temple authorities on the other hand saw that it was aimed directly at them and at their atfhority and used political blackmail to fget Jesus killed. I think the NT account is a trustworthy one. Pilate was not the sort toi have scruples about victimisingan innocent man if that saved his own skin but like most Romans he had nothing but contempt for religious squabblefs among Jews. It is significant that he too k no action against the followers of Jesuis. aJf<esus was not interested in a direct confrontation with Rome because that could only leas to violence. His brother James took the same line and he was killed by the same Jewish authorities who had engineered the death of Jesus. As Pilate well knew they were highly untrustworthy "collaborators" who had an anti-Roman agenda of their own and it was they who, sfter getting the reespected and popular James out of the way, started a disastrous rebellion of their own. Traditional anti-semitism assumes that the Jews as a whole were responsible for the death of Jesus whereas it was only a tiny and highly unpopular minority.

Gannhi on the other hand always had Indian independance fom Britain as a primary political aim and he was prepared to acce[t that this might be accompanied by violence even though his personal commitment was religious and pacifist and he never ceased to proclaim that. x It was not a politica;opponent but a Hindu fanatic who killed hi.

As regards the Nayler affair Cromwell and his army had the real power but although he had little sympathgy for the fanatics in Parliament he was not yet ready to turn them out and let them have their way. He was more principled than Pilate but 'twas ever thus in in politics.

Dear Mike,

Thank you for your useful comments for which I have a great deal of sympathy.

Shalom,

Stuart.

Hi Stuart. I enjoyed this. I agree with you about comparing Jesus overturning the tables in the Temple with Naylor riding into Bristol. Just a word of comment about the way you have told the stories of the heroes and heroines you mention, including Rosa Parkes. Some historians, mainly on the left of centre, caution against the myth of heroes and heroines single-handedly changing the world. They suggest instead that each of these so-called heroes and heroines are backed up by multitudes of people and years of struggle. I think that was true in Rosa Parkes’ case: she’d been in the NAACP for years before taking her stand (or seat) on the bus. Not that this detracts from your point. If anything, it clarifies why these heroes and heroines are so dangerous to the establishment: they are dangerous because they represent the views of their many supporters. In friendship, Robbie

Dear Robbie,

I very much agree with your comments about the dangers of paying too much attention to individuals and neglecting the community/movement that enables them to be who they are. In this case I felt I had to use individual examples (Jesus, Gandhi, Parkes and Vanunu) because I was seeking to defend an individual’s actions (Nayler).

Shalom,

Stuart.

One thing you point out — that Jesus went into Jerusalem expecting to suffer death in God’s service — has struck me as key for some time now.

Naylor, I am sure, was fully aware of the implications of this, and probably likewise expecting martyrdom. The unfortunate immediate consequences to the Quaker cause — which may have been far more mixed with good than we realize — were not within his power to predict; but that he was making a witness he expected to cost him his life does suggest ‘acting in Jesus’ spirit’, so far as “take up your cross and follow me” can embody that. (Obviously this was not Jesus’ entire message…)

So, it was really Fox and the Society which “fell” in the course of this trouble, so far as anyone did. Naylor’s leading would seem necessarily as genuine as anyone’s — except that he may not have truly understood its purpose either at the time nor afterwards. (Consider Fox’s leading to take off his shoes and cry out “Woe to the bloody city of Lichfield” as he passed through there…. Infallibility doesn’t seem to be a necessary feature of faithfulness.)

Dear forrest, apologies I have only just seen your comment. I agree that faithfulness is often more important that concerns about impact or success. Obviously good discernment if essential but we also have to humbly accept that our understanding is limited. Stuart.

I agree with Stuart Masters.

In the BBC Broadcast In Our Time “George Fox and the Quakers†on 5.4.2012 one of the (unidentified) participants from Melvyn Bragg, Justin Champion, John Coffey, and Kate Peters said, “Nayler thinks he is perfect. Because he has Christ within.†To my mind, this is indicative of the calumny currently the norm when people speak of James Nayler (1616-60). Far from thinking that the Christ within made him perfect, in the way the Ranters believed for example, James Nayler was a modest man, mostly aware of his imperfections.

It is strange to think that such an important member of the Valiant Sixty should be so denigrated, as he was by non-Quakers then and as he sometimes is by Friends these days. As Christopher Hill has written, in the 1650s many regarded Nayler as the chief leader, the head Quaker in England. In December 1656, Colonel Cooper told Parliament, “He writes all their books. Cut off this fellow and you will destroy the sect,” Another opposed to Friends, Thomas Collier, wrote in 1657 that James Nayler was “the head Quaker in Englandâ€. Despite George Fox so often now being called the “founder of Quakerismâ€, in the early days of the movement he was not successful in London being considered odd and uncouth whereas Nayler could move easily among urban society. Nevertheless, although Nayler had been better known amongst the general public than Fox, both as a preacher and as an author, among established Friends, Fox was considered the leader. After Nayler’s trial and punishment, some leading figures such as Richard Farnsworth disappeared from view for several years, perhaps because he was uncertain where his loyalties lay and it was then completely open for George Fox to take-over. Such an appropriation led to much greater exercise of control by London. Many of those who did not agree with Fox’s tightening of discipline, such as Perrot, Rich and Byllynge, emigrated either to the West Indies or in the last’s case, to New Jersey. Some, such as George Bishop stayed, despite their misgivings. Many died, such as Nayler, Burrough, Hubberthorne and Fisher, which left only George Fox unchallenged as leader. The new generation of Penington, Penn and Barclay were not in a position to challenge him, even had they wanted to, which I doubt. Christopher Hill believes that Fox’s maneuvers against James Nayler and John Perrot were smear tactics – denigrating but not expelling. Fox also set about, from 1672, to censor previous Quaker publications. Perhaps this was pay-back for the fact that, as a sign of his disapproval, Nayler kept his hat on when George Fox prayed in Meeting. This was quite separate from the Perrot controvosy.

As a result of their proslytising success, Nayler and Fox both received adulation from their followers some of which seems entirely inappropriate. For example, Hannah Stranger sent Nayler a letter that was used as evidence against him in the magistrates’ court after the Bristol incident, which said, inter alia, “Oh! Thou fairest of ten-thousand, thou only begotten Son of God …” According to George Whitehead, the praise Martha Simmonds gave James Nayler turned his head. But she was also useful. When employed as a full-time nurse by Oliver Cromwell’s sister, the only payment she would accept was the release of Nayler from Exeter jail. However, she could prove disruptive. While she was nursing the wife of Major General Desborough, the commanding officer of the district of Exeter where Nayler was in jail, she attacked George Fox at Launceston, telling him to subordinate himself to Nayler. Unsurprisingly, Arnold Lloyd suggests that both Martha Simmonds and Hannah Stranger were Quaker women who exerted undue influence on James Nayler. In the same way, however, Margaret Fell, two of her daughters and four other Friends wrote entirely improperly praising Fox in extreme terms. Notwithstanding the adulation, it is clear that neither man was so saintly as to deserve the extraordinary praise they received from some Friends. For instance, Nayler is accused of having fathered a child with a Mrs. Roper while her husband was away on a voyage for 47 weeks. And as a young man, George Fox could be egocentric. For example, when visiting a Dr Craddock in Coventry, he stepped on the doctor’s flowerbed and justified himself by commenting that the doctor’s anger was disproportionate to “the great questions of life, death and eternity.†George Bishop, army captain and Bristol Quaker, a supporter of both Fox and Nayler, places the cause of Nayler’s “fall” fairly on the women who surrounded him. This misogynistic view seems to be the norm.

Whatever the adulation, it must be recognised that a failure in judgment by James Nayler led to his downfall. When hauled before Bristol magistrates, they clearly did not understand each other, because when he talked of being the Son of God he meant the spirit within himself but the magistrates took it that he was claiming actually to be Jesus. Nayler explained both to the magistrate and subsequently to Parliament “that his entry into Bristol was intended as a symbol of the coming of Christ as a living reality.” In one part of the evidence where it was represented that George Fox had affirmed that Nayler had called Martha Symonds “mother†in the sense of Mother of God, Nayler replied that, “George Fox is a lyar and a firebrand of hell; for neither I, nor any with me, called her so.†Such remarks were to rebound on him many years later. Straight after that exchange, Dorcas Erbury (daughter of Friend William Erbury) testified to the magistrates that she had been dead two days when James Nayler raised her from the dead by saying “Dorcas, arise!†and that she had accompanied him in his progress into Bristol. However, other sources have suggested that she had just been in a faint. Anyway, Nayler never claimed that he had raised her from the dead.

Returning to Hannah Stranger, she and her husband wrote to James Nayler and ended the letter with, “Thy name shall be no more James Nayler but Jesus.” When he was arrested after arriving in Bristol the letter was still in his pocket and this was possibly one of the reasons why the magistrates sent him to London where a committee of Parliament debated his fate for nine days. Cromwell said that Parliament was acting illegally in trying him, as it had no judicial role. In the BBC In our time broadcast, it was said that Cromwell intervened to prevent Nayler’s execution because he might be the Christ although the source for this extreme idea was not given. However, because of Parliament’s failure to take note of Oliver Cromwell’s objections to their trying James Nayler, the broad problem of arbitration between Parliament and Cromwell when they disagreed, came to the fore. The result was the Humble Petition and Advice, part of which was to offer Cromwell the crown.

The Parliamentary trial of James Nayler was a typical example of mob hysteria. Every fear of the Quaker challenges to the establish church and magistracy came out. During it, Colonel Robert Wilton, for example, described Quakers as, “These vipers are crept into the bowels of your commonwealth, and the government too. They grow numerous, and swarm all the nation over; every county, every parish.” Such venom inevitably led to a really harsh punishment short of execution taken by many Quakers of the time to be a parallel with Christ’s crucifixion.

After Richard Cromwell abdicated in May 1659, a handful of survivors of the Rump Parliament constituted themselves as a Parliament and sat until October, when military rule was again imposed. It was this body, responding to a short-lived mood of religious tolerance that set free Nayler and more than a hundred other Quaker prisoners. The date of his release was September 8, 1659, nearly three years after he was first imprisoned. He then met Fox who made him kneel before him. To my mind, that does not show Fox in a good light. As Leo Damroch has said, “In effect the Quaker leaders had developed exactly the same kind of authoritarian ministry they had originally opposed. … After 1660, when Fox was securely acknowledged as leader of the movement, its earlier history was reinterpreted – and some inconvenient documents probably suppressed – in order to antedate that role to 1650 or even earlier, but in fact he had been honoured as a co-worker [with Nayler and others] rather than a leader or prophet with special authority that others did not possess.” James Nayler, in the meantime, despite his spirituality and role in establishing Quakerism, has been relegated to a very minor place in the history of Quakerism.

Dear John Hall, thank you for your comment. Sadly I think you are right about the injustice associated withf the relegating of Nayler’s significance to the early Quaker movement. It seems to me that early Friends were claiming that only Christ could be head of the church and so all human leadership could only ever be provisional. During the ‘Bristol episode’ Nayler appears to have adopted a radical form of surrender and passivity that is comparable in many ways to that of Jesus in the lead-up to his passion following his outward prophetic action in the Temple. The Fox and Nayler positions demonstrate a dynamic tension that needs to be maintained within the Quaker way between passive inward surrender to the movement of the Spirit and an outward active life lived in the power of the Lord. Who best maintained this tension; Fox or Nayler? I don’t really think the answer is easy or straight-forward. However, Nayler’s conduct appears entirely in keeping with first generation Quaker faith and practice. Stuart.

I’ve always thought Nayler got a bad press. I remember reading as much in a book some years ago. I think the accommodation Fox and followers negotiated served well during the Quietist years in establishing Quakerism as a private practice. Other previously persecuted (Catholicism, Judaism) and currently persecuted (Islam) minority religions are also required by the Establishment to sign up to the idea of religious practice as being an entirely private thing – not impinging on outward life during the week. This is not, by and large, what Quakers want to do.