The Constitutional System in New Zealand

l We follow the British tradition, very unusual among nations, of not having a written constitution. In fact our constitution is based heavily on the British one, so it is a mix of ancient documents (Magna Carta, the 1688 Bill of Rights, etc) and “constitutional conventions†(the way things have traditionally been done).

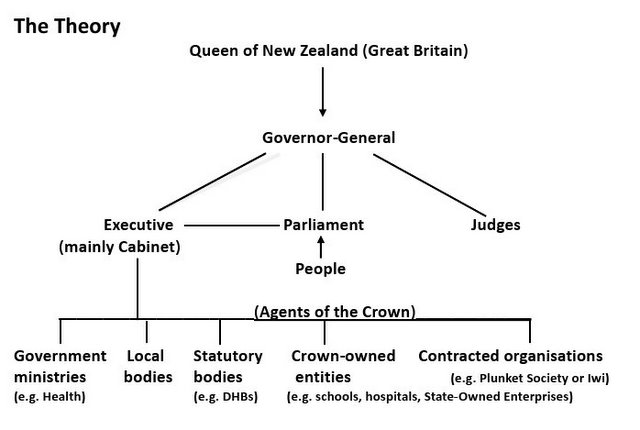

l The people elect our Parliament, and we are therefore in principle a democracy.

l Parliament makes and unmakes our laws by legislation; but legislation must be signed off by the G-G or the Queen before it becomes law.

l The Queen and the Governor-General act only on the advice of their Ministers, so cannot refuse to sign laws which Parliament has passed.

l The main part of the Executive is the “Ministers of the Crown†(mainly in Cabinet).

l The Ministers are all MPs and remain part of Parliament; they introduce all new legislation other than Private Members’ Bills.

l Legislation in most circumstances goes through a Select Committee process, where anyone can make a submission for or against it, and can ask to appear in person to speak to their submission.

l The Ministers are each responsible for one or more portfolios, e.g. Health. They are responsible for the administration of their portfolio, which is carried out through the various “agents of the Crownâ€. These bodies are accountable to the relevant  Minister through legislation or contractual obligations.

l The Judges hold warrants as “the Queen’s Judges†and these cannot be withdrawn except in the most exceptional circumstances. This keeps them politically independent.

l The Courts cannot challenge a law passed by Parliament, but must interpret it to fit the cases that are brought to them.

l When there is no relevant legislation, the Courts apply the Common Law. In Aotearoa New Zealand there are two sources of Common Law: one based ultimately on the customary law of England, handed down from time immemorial but re-interpreted by senior judges in every generation to fit new circumstances, therefore often described as “judge-made lawâ€; and also, in former British colonies such as ourselves, the customary law of the indigenous people of the country.

Â

Why it doesn’t work in practice

Why are we so dissatisfied with our elected representatives? Why does Parliament make laws which in some cases are opposed by the majority of the people?

- Most nations have two houses of Parliament, and one important function of a second chamber is to make the government slow down and think more carefully about some of its legislation. Our second chamber was abolished in 1951. By taking “urgencyâ€, a New Zealand government can pass all the stages of a piece of legislation very fast. The present government has used urgency 17 times in two years, a much increased rate over previous years. Legislation is often shoddily drafted and needs amending later on.

- Because we have no written constitution, our government is always tempted to push the boundaries of constitutional convention (i.e. the way things are supposed to be done). Also, our Courts cannot challenge or strike down legislation by finding it unconstitutional.

- Because we have a small number of MPs by international standards, the Ministers form a large fraction of the ruling Parliamentary parties, and through numbers, more information, and control of patronage and promotion, can control their back-bench colleagues to an extent no British government (for example) could dream of.

- New legislation and policy often begins with a small number of the Cabinet Ministers who actually have the trust of the Prime Minister of the day. It then goes for approval to the whole Cabinet, and once it has been voted on there, the doctrine of collective Cabinet responsibility demands that all Cabinet Ministers support it, even if they actively opposed it up to that point.

- The next stage is that before anything reaches Parliament, it goes to a Caucus meeting of the majority party in Parliament, in other words to a meeting of all its MPs, in which Cabinet can exert its controlling voice. Again, when Caucus approves a measure all its members have to speak and vote in favour of it, just as all Opposition MPs have to follow the decision of their Caucuses. Only in a few special cases (usually about liquor or moral issues) are MPs allowed to vote according to their personal consciences and beliefs.

- The Select Committee process is meant to be a democratic safeguard, a place where citizens and expert resources can have a say about impending legislation. However, governments normally hold a majority in each Select Committee, and the Committee’s report is referred to Caucus before going back to Parliament. Over 90% of submissions on the 2004 Foreshore and Seabed Bill opposed the Bill, and despite that it went straight through into law. That is fairly typical; so are other manoeuvres to blunt the effect of the Select Committee process.

- The result of all this is that the Executive is in fairly complete control of Parliament and the laws it makes. Proportional representation under the MMP system has made some improvements in the quality and variety of our MPs, and has enabled some minor parties to be represented and to take part in Government, but has not changed the total picture. Parliament itself is effectively sidelined into being a permanent election campaign, hence the excessive competition and empty noise.

- Meanwhile Ministers are subject to many pressures for policy and legislation, few of which have much to do with the people. The pressures come from our international obligations and treaties, from international business groups and other governments, from local corporates and business groups, and from a multitude of lobby groups. About 25% of new legislation, for example, comes from our international obligations and treaties.

- The people do not select the candidates they choose among. That is done by the political parties, whose total membership may be perhaps 10% of the voting population. The really active party members, those who influence policy and selections, may be 10% of that membership. It’s a very narrow base.

- What the people know about what government does is mainly transmitted through TV, radio and the press. TV and the press live and die by advertising revenue, and competition for that, in the absence of real public broadcasting (except for National Radio, MÄori TV and TVNZ7) leads to superficial and sensationalised treatment of public issues. Even if issues are presented without undue bias, coverage is so brief and bitty that the public is left confused. Without much need for conspiracy theories, the result is what Noam Chomsky described as “manufacturing consent†– or at least making coherent and broad-based dissent extremely difficult.

- Relationships with other nations, including peace, war and treaties, are the preserve of the Queen and her Ministers, and Parliament has no say in them unless Cabinet chooses to involve it (as it increasingly does). Treaties (including the Treaty of Waitangi) have no place in our legal system unless Parliament has passed legislation which embodies them in our internal law. Hence the inconsistent treatment of the Treaty of Waitangi, recognised in some Acts but not in others.

- The whole system described here is based ultimately on the kawanatanga provision of te Tiriti o Waitangi, which gave the Crown authority to establish itself here. There is no provision in the constitution for the countervailing authority of tino rangatiratanga, promised to the structures of the MÄori world in te Tiriti. All MÄori participation in government is as a minority operating wholly within the Crown’s structures.

- The end result is what Geoffrey Palmer (former Prime Minister and public law expert) has referred to as “elected dictatorshipâ€, almost as much so for non-MÄori as for MÄori.

This document accompanies the article Constitutional review: an opportunity for influence.